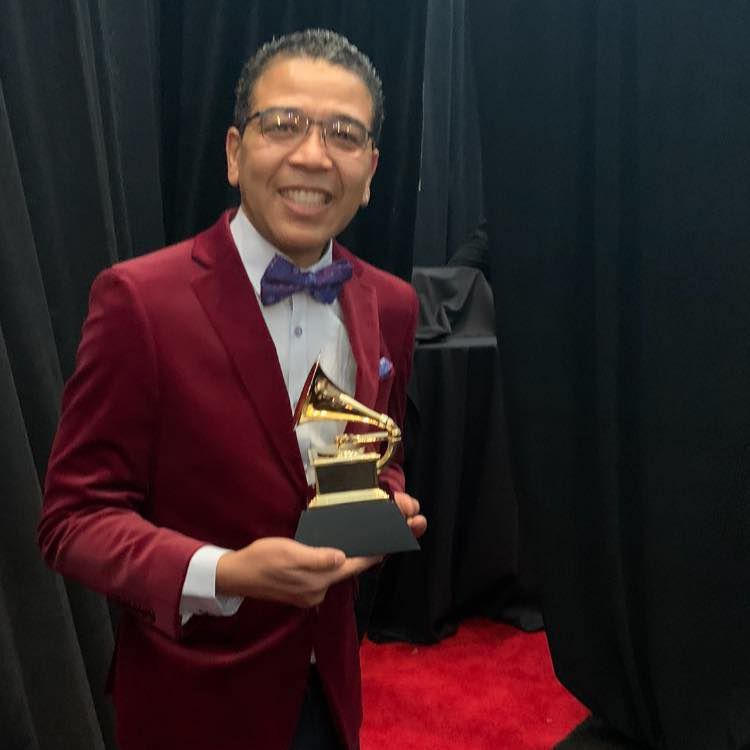

From growing up in a musical family in Venezuela to performing with some of the all-time greats like Chick Corea, Tito Puente and George Benson, percussionist Luisito Quintero lives to find the unique grooves underlying all moments in life. Quintero has earned international acclaim for his signature timbale technique and racked up numerous Grammy nominations for his work with 3rd Element and Quintero Salsa Project. We sat down with Luisito to learn more about his inspiring musical journey and what drives his creativity.

How did you first get involved with music?

I come from a very musical family in Venezuela. My grandparents, my father, my uncle—everyone in my family played music or sang. I grew up with music all around me. Venezuelan music has a distinct rhythm and an emphasis in percussion. So in my family, we’re all taught from a young age to play percussion in addition to playing a harmony instrument like bass and guitar.

Now I get to play alongside my cousin Roberto in the Quintero Salsa Project and 3rd Element, so that family connection is still strong. And it continues to the next generation—my son and nephew are learning to play drums and percussion.

How did growing up in a musical family influence your decision to pursue music as a career?

I started playing when I was three years old. Since I was a child, I felt a passion for music in my heart, and as I grew older, my passion for music grew too. I got to play on my first recording session when I was twelve years old! My uncle took me to the studio just so I could see how the music is recorded. The band was recording a song that needed congas or bongos, but no one was available to play them. My uncle convinced the band to let me—this twelve-year-old kid—sit in on bongos, and that was amazing. After that I just knew music was what I wanted to do with my life.

How do you approach your role as a percussionist when playing with various ensembles?

Percussion can play different roles in different types of music. Over the years I’ve collected many types of instruments from Brazil, Venezuela, Africa, India and all over. I like to put together a custom setup for each musical setting I’m invited to. If there’s already a drummer, I’ll bring bongos, congas and timbales.

If there isn’t a drummer, I’ll bring a hybrid drums and percussion kit with cajon, snare drum, congas and cymbals. That’s a trick I learned from my uncle. He played a hybrid set up with a kick drum, snare, two congas, djembe and cymbals. People called him “the octopus” because when he played it sounded like he had eight limbs—like two percussionists playing at once. I modified his approach, replacing the kick drum with a cajon, and put my own style into it.

I focus on listening to what’s happening between everybody, and then I try to engage and work with the groove the musicians are creating, in the context of the song itself. When you’re really listening, it’s easier to respond to your fellow musicians.

How do you keep your musical ideas fresh?

I listen to all types of music every day and I try to learn from what I hear. I pay attention to the different rhythms and patterns, whether it’s jazz or Latin music. I’ve been listening to a lot of older music, especially from the ‘60s and ‘70s—they had such interesting and unique grooves back then. When music is recorded with a metronome, as is common today, the rhythm can sound digital and artificial. It’s rare to find grooves today that sound like the ones you hear on those old records.

When I get called to sessions, sometimes the producers and other musicians tell me that I’m bringing new sounds. But the truth is, I just try to channel the organic sounds of those older recordings and put my own twist on it. When I record with Spanish Harlem Orchestra, Chick Corea or Quintero Salsa Project, we always record live without a click track. When you record live as a band, you really capture the special moments and connection between everybody in the studio—the recording has soul. Beautiful things happen when you record live.

What kinds of challenges have you faced in your career?

I believe the greatest challenge is to make sure that when I play, other people can feel my groove. Sometimes you’re playing, and you put everything you have into it, but the people feel nothing. It’s important for me when I play timbale or bongos that the other musicians and the audience are reacting to what I’m playing. You can feel when that happens, they will give you back the same energy you’re giving to them. This is the most challenging aspect to what I do, but it’s also very rewarding.

What advice do you have for newer percussionists or musicians looking to form a band or perform for hire?

I always tell the young musicians that practice is important, but listening is even more important! Listen to the old music from the ‘60s and ‘70s and study the interesting grooves and sounds. Many young musicians have a lot of talent and very impressive technique, but if you don’t combine that with serious listening skills, the musicality won’t shine through.

In New York, it’s common to get a 911 call from a producer. This means that someone didn't show up for a session or one of the players isn’t cutting it. So they call you and you need to come right away, like an emergency. You hurry to the studio, and you don’t know what to expect. They may have sheet music and expect you to sight-read it and play it right the first time. And you don’t know who you’re going to be playing with—you may not know any of the other musicians, or you might walk in and there’s Christian McBride. It’s important to keep your nerves and always perform at your highest level.

Modern technology has enabled musicians to work remotely on studio recordings together. How do you approach this kind of collaboration? How does it differ from recording in the studio together?

It can be quite different, and sometimes it can be weird. But if the other musicians send you a good file to play along with, it can work out really well. I always try to imagine that I’m actually playing with the other musicians, even when I’m recording alone. Sometimes they’ll send me sheet music and the part I’m supposed to play is very clear. But other times, they might just send me a track and let me play whatever I feel. When this happens, I spend time listening to the track for a few days and study the charts until I can feel the music growing inside of me. Then I’ll go to the studio and record that part in one complete take—I prefer getting it all at once to editing together separate parts.

What Zoom gear do you most commonly use?

I have the Zoom Q2N-4K video recorder and H4N audio recorder. When I’m recording videos for remote sessions, I use two Q2N-4K cameras to get multiple camera angles and I send them to the project video editor. I use the H4N to record rehearsals and live performances. When I listen back to these recordings, the sound quality is so clear, I can actually hear the subtleties of the groove. The top end sounds like it was recorded with studio microphones—it’s amazing!

Can you share anything about any recent or upcoming projects?

I’m staying busy with recording projects, —later today, I’m going to the studio to record the score for an upcoming movie by Sony Pictures. I was recently involved with an ambitious Latin Jazz world orchestra project, with amazing musicians from all of the world recording their parts remotely. I also have new albums coming out soon from 3rd Element and Quintero Salsa Project!