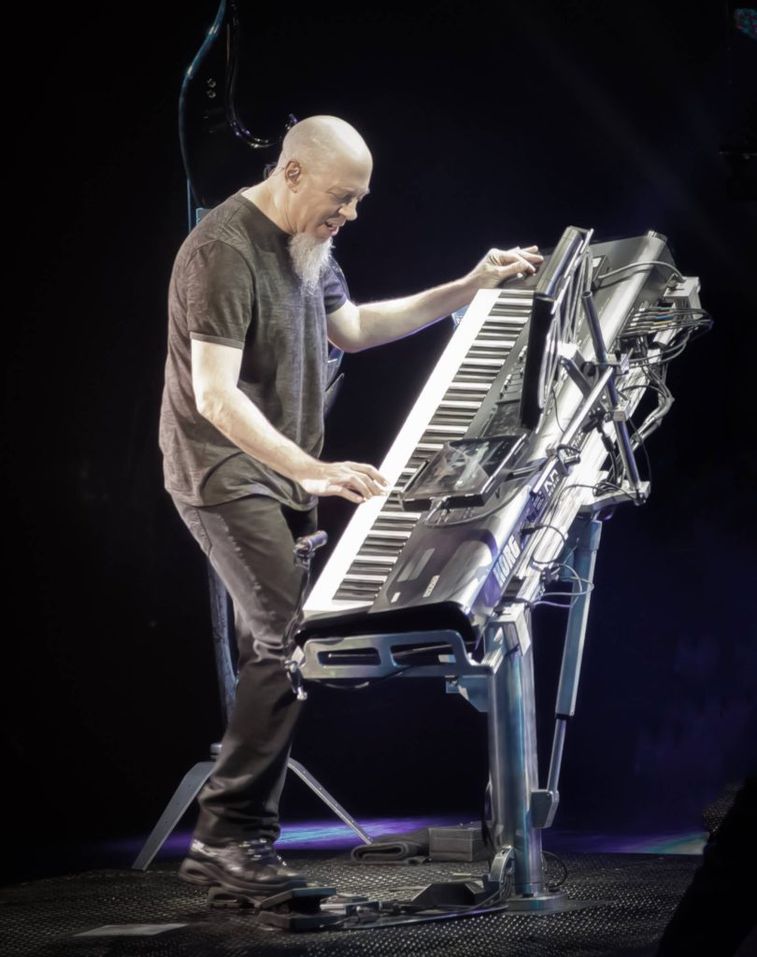

From his classical beginnings to current status as an icon of the progressive rock world, keyboardist and sonic pioneer Jordan Rudess has always followed his creative instincts to create some of the most forward-thinking music of this century. In addition to his role as a member of Dream Theater and Liquid Tension Experiment, Jordan has also recorded and performed with a diverse list of artists including David Bowie, Vinnie Moore, Steve Morse and more. We recently talked with Jordan about his unique career path from Juilliard to Dream Theater and learned how he’s forging his own path by creating revolutionary new instruments and embracing intimate connections with his fans through streaming and music lessons.

How did you first get involved with music / keyboard?

I first got involved at a young age. I don’t come from a musical family, but my second grade classroom had a little upright piano in it. I was drawn to that piano. I would go in every day and play that piano. One day my teacher called my mother and said “Jordan is playing the piano really beautifully in the classroom. It’s very nice.” My mom said, “Jordan doesn’t play the piano, we don’t have a piano.” And my teacher said, “Well you should get one because Jordan is playing quite well.”

So my mom bought a piano that week. It was a very nice baby grand piano. I started taking 30-minute lessons from a local teacher. Within the first year, that guy threw out the lesson book because he recognized I had a good ear and he started to show me all the chords. And I learned how to just find the chords and improvise.

Somebody who did know about music came over to the house and saw me playing piano from a guitar book that just had a single melody line and the guitar chord symbols. I was making up my own arrangement. He said, “How are you doing that? It doesn’t say that on the page.” I’m like “What do you mean, I’m just playing.“ And he said, “No, none of what you’re playing is on that page.” I thought everybody did that! That was how I found out that what I was doing was a little bit unique.

After that I started going to a serious teacher who was determined to get me ready in one year to go to Juilliard. So I was eight years old and studied with this Hungarian pianist that really wanted to get me into the school. She taught me for about a year and a half. And before I turned ten, I auditioned for the Juilliard pre-college and I got accepted. That started me on my path to actually becoming a classical pianist. It was a very serious foundation and classical upbringing.

So I had started with improvising different kinds of popular music, and then went into full-on classical mode—although I was always still a closet improviser! I’d have to go to the furthest room down the hall away from all the teachers to play boogie-woogie and blues and whatever else was going on in my head. That was kind of like the beginning of it.

When I got to Juilliard, I realized that I was surrounded by kids that were nine years old and writing operas. There were incredible young musicians from all around the world that were playing Liszt piano concertos and other ridiculous things. I was lucky to be a part of that group and have a great teacher. That foundation is really the basis to everything that I’ve done my whole life. I’m extremely grateful. Even though I left the purely classical world, what I learned there has been invaluable.

What were your first professional opportunities as a musician? How did this impact your development?

When I was at Juilliard I was doing a lot of concerts and recitals. I was taking on little professional performances, as much as a kid really could. At the age of 13, I appeared in a Johnson & Johnson commercial, playing in the Plaza Hotel grand ballroom on a nine-foot Steinway with a Band-Aid on my finger. You can still find that commercial today if you know where to look.

One of things I did early on was work for Korg and Kurzweil as a product specialist, doing demos and presentations. I would do a big performance to show off one of their keyboards. In doing that, I started getting a lot of press for these performances.

That news reached the guys in Dream Theater, in addition to some people in their circle telling them about me. Even their original keyboard player had mentioned my name to them. So between them reading about me in Keyboard Magazine and hearing from people they knew, that’s when they originally reached out to me.

So they ended up calling me up and having me to come down to audition for them. I didn’t really know who they were at the time. I had to do some research and find out what they were all about. I auditioned and ended up playing one gig with them because they really needed someone to fill in when the first keyboard player left. But at that time I decided not to join the group.

Instead, I joined a group called the Dixie Dregs with Steve Morse. They were a successful instrumental band that I was very aware of. I thought the Dream Theater thing was cool but it wasn’t the right time for me, I wanted to go off and do some other things.

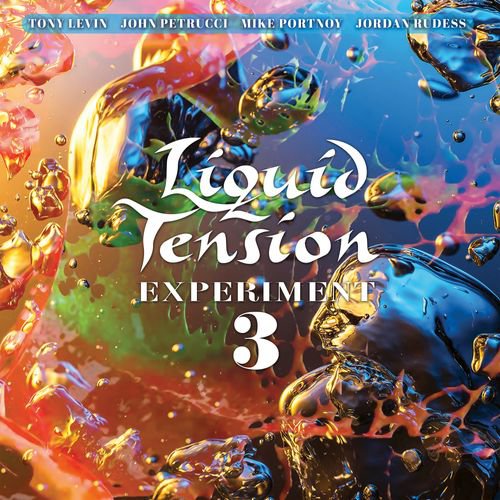

Meanwhile I stayed in touch, and one day I got a call from the manager representing Mike Portnoy, the drummer of Dream Theater at that time. They asked if I wanted to join a “supergroup” with Mike on drums, Tony Leven on bass, John Petrucci on guitar and me on keyboard. So it was two guys from Dream Theater plus Tony and me. I said yes to that and it was a pretty important project for me.

We released two successful albums as Liquid Tension Experiment, and then after that they asked me again if I wanted to join Dream Theater. At that point I said yes. I liked working with those guys, we made some cool music together, we had some success and it was a better time for me personally.

It was the end of 1998 when I joined. In 1999 we released Scenes From A Memory, which was the first Dream Theater album I was involved with, and it was a big success—to this day it’s one of DT’s most successful albums. That’s how I came to be a part of Dream Theater.

Who and what are your biggest inspirations and influences on the way you approach the keyboard?

When I left Juilliard I opened up to a lot of artists beyond the classical world. I got really into Chick Corea, who we unfortunately lost recently. Even though I’ve never been a big jazz fusion guy, one of his albums in particular Now He Sings, Now He Stops was very pivotal in opening me up to new possibilities that I could go into with chords and rhythms. My most forceful inspiration was Keith Emerson and the Tarkus album he did with Emerson Lake and Palmer. That was the first time I heard the kind of power and might one could have with keyboards. Some other guys that influenced me were Rick Wakeman and Patrick Moraz. As far as bands go, certain groups at that time were major influences bringing me to where I am today, like Genesis, King Crimson, Yes and Gentle Giant—these amazing, progressive rock groups. I saw multiple concerts of Gentle Giant, I thought they were so cool. They all played different instruments and there was a lot of counterpoint going on. It was kind of mind blowing because there’s just not enough counterpoint in rock music.

How do your musical ideas evolve? What happens between the initial idea for a project and the finished product?

In the progressive world, it’s accepted to have really long songs that are more similar in form to classical compositions than pop songs. I enjoy taking a motif or some kind of musical passage and seeing what can be done with it. I might take the melody from the right hand, and see what happens if I put it in the lower register and add something else on top that turns it around. I’m interested in all kind of different compositional techniques.

When I was creating my last rock solo album Wired From Madness, I started the album and I didn’t know what I was going to do. I just wanted to start working. I got in front of my computer and I started to record and I wrote 30 seconds of music. Every day I would listen to the previous 30 seconds and I would get inspired to come up with something to follow it. After a while, I had about eight or nine minutes of this continuing thing that was happening from day to day. It didn't seem like it was ever going to wrap up! I walked in the house one day and I told my wife that I was writing this piece that I don’t know where it’s going to end. I thought maybe the entire album could be just this one piece. She said, “You can’t do that, you have to write some songs. Some people want to hear songs as well. Don’t make the whole album this crazy continuous one piece.” I thought, “Maybe she’s right, maybe I should write some songs. I can’t have the whole album be this.” I finally figured out that this one piece could be 25 minutes, but the rest of the album should be some shorter songs.

Basically, there’s no shortage of inspiration. I can walk in and improvise something, then play it into my DAW and I can see the notation and start orchestrating it. It’s really a matter of decision-making and figuring out what the structure is going to be. I can sit down at the piano and just play whatever comes in my head, and that’s cool for streaming and jamming, but in composition process, I have to make decisions. One of the things that’s really important is to not get hung up on things like obsessing over this chord or that chord. I know a lot of talented players can never finish anything because they can’t make a decision!

In addition to massive discography with Dream Theater, Liquid Tension Experiment, and your own solo albums, you’ve collaborated with a diverse list of artists. How do you adjust your approach when collaborating with different groups of musicians?

One of the things about the way I approach music is that I’m very open stylistically. I love all kinds of music. Music is totally my life. The prog-metal side of me that most people know about is really only a part of who I am musically—it’s not all of who I am! I also love solo piano, electronic music and mellow rock music. Depending on what I’m doing, I try to be as open as possible.

It’s really important to be able to fill a particular musical need. If I’m working with a producer, I need to understand what they want and what they’re asking me to do. I try not to have an ego involved in the performance. That could take me out of the space of understanding what the actual job is in the studio. Even in Dream Theater, someone might have a particular vision that I’m trying to follow. Because every member needs to have a say in this sonic fantasy we’re creating, I have to try to understand their ideas and articulate them as best as I can.

When I worked for David Bowie, I came in very excited of course. Going in, I had this fantasy that I was going to change his musical world and be the next evolution of his career. When I got there, I realized that he and the producer had something really particular in mind for the way they wanted this album to sound and the role the keyboards would take. So I had to adjust my energy and expectations to fit in to their vision—which I did and I learned a lot from that.

In the Dixie Dregs, I played with Steve Morse, one of the world’s greatest guitar players. He taught me, when someone is taking a solo, you have to lay back, turn down and really chill because it’s their turn to shine. That sounds relatively simple in concept, but it’s an important lesson that everyone needs to be aware of and put into practice.

Music is something that is so beautiful and nobody should be denied the right to make as much music as they want to make."

You’ve not only pushed the boundaries of music performance and composition, but you’re also known for innovative uses of technology in music. Through your work with Wizdom Music, you’ve helped to bring new instruments and music software into existence. What inspired you to get into the world of creating new instruments and how has it influenced your own music?

One of the things that really changed my life was when I discovered the Moog synthesizer, specifically the Minimoog. I had to convince my parents to figure out how to get a Minimoog. This was when I was first leaving the classical world and getting into other things. That synthesizer really changed my life. I realized that I had a strong connection with the art of expressing sonic ideas by turning knobs and listening to the sound change. I became more and more aware of the way that sound happens from that point of view. The electronic headspace is very different from the acoustic headspace, and it comes with a whole new world of possibilities. I became passionate about playing the Minimoog and exploring synthesis. It led me on a path to always being interested and involved in the development of instruments. I worked with Korg and Kurzweil, programming sounds for their instruments and making suggestions for how the instrument should behave and operate.

A lot of things progressed quickly when I discovered the first iPhone. Before it had any good apps, I would just put my hand on it and move my fingers and imagine if I could just push my fingers in different directions, I knew there’s something really cool that could happen musically. This was in the early days of the iTunes app store. I found a guy that was doing some music programming. I reached out to him and told him I had an idea of how to create music on the iPhone. My idea was a multi-touch experience where every note could be independently played and you could apply pitch bends or vibrato to one note but not the other.

The app we ended up developing was called MorphWiz. Billboard voted MorphWiz as the #1 music app that year. It opened the door to being able to develop more ideas. So we did a sampling app called SampleWiz. Now I have an app called GeoShred. It’s a very expressive musical instrument that runs on iPad and iPhone, soon on Android.

I’ve used all of my apps in my own music. I used GeoShred in my rig on the last DreamTheater tour. I could play leads or introductions to different songs on it. I’m making these apps for the world but I’m also making them to use myself. It started with the interest in electronic music, then I became really passionate about how technology can further expressivity in music.

When you put these things out, you have no idea where they’re going to go. One of the most rewarding things about GeoShred is that its become such a real instrument that there are new musicians that are GeoShred players—that’s their main instrument! Especially in places like India, where they’re more sensitive to pitch, Carnatic musicians have a really advanced way of controlling pitch in a mixture of diatonic and fretless scale systems. GeoShred really allows that kind of playing like nothing else. It has this really intelligent pitch bending. So I see videos of people playing GeoShred in India and it blows my mind because they’re doing amazing things—things that I can’t do myself! It’s really rewarding.

Modern technology has enabled musicians to work remotely on studio recordings together. How do you approach this kind of collaboration?

Sometimes I get asked to do solos on other people’s albums and I usually do that remotely. I’ve also worked on some really important albums, I did two trio albums with Tony Levin and Marco Minnemann, those were all done remotely, we worked in our own studios and sent files back and forth. It’s nice to be in your own studio and just focus and do your thing. Network technology has improved so much. As far as being able to talk and share ideas with someone else in real-time and lay down tracks, it’s all coming to the next level.

You recently started a Patreon that grants access to your musical world, including livestreams, live chats, lessons and tips for musicians. How important is sharing your knowledge and engaging with the next generation of musical innovators?

One of the things I’m really passionate about is sharing. I love so many things about social media and the ability to reach people and connect with them. I’m a people person. I like interacting. I find that a lot of the people that listen to my music are people I want to talk to and communicate with. In the modern world, as a person who has a following around the world, it’s difficult to remain in contact with everybody. So I set up a Patreon because I thought that was a great way to bring people who are especially interested and wanted to give something back. The idea was to set up a line of communication and get into discussions with people, but through this more focused medium of Patreon, which has been amazing.

I find that people that come on to my Patreon are especially dedicated and I’m very happy to communicate with them. I’m happy to communicate with anybody but there’s only so much time in the day to check all the different social apps and respond to everything that’s coming in. There’s just no way I can do that. Using Patreon to bring focus back to these interactions has been great.

What kind of affect has the pandemic had on the music industry, and how you've had to evolve with the current time?

As a message to the music industry I think it’s really important because when the pandemic first hit, everybody was staying home and locked down. I got really into sharing music by just turning on my phone and doing a Facebook livestream. I was doing it like everyday, just playing my heart out to who ever wanted to listen and share. I felt great about that, I still do. At some point along the way, maybe after doing that 50 times in a row, I started to think that as much as I love this, music shouldn’t be completely free. As a musician, I felt one of the most important things I could do was to say, “Look, I’ve enjoyed this. But if you really want to come into my world, see all my streams and be part of my musical life, it’s going to be on Patreon. It gives you a chance to give back to me, and I’ll continue streaming, I’ll share lessons and exercises and I’ll be in touch with you. But that’s the way I want to do it.

Over the last eight months I’ve helped create an awesome online music community, which is still growing. I feel very satisfied with that. It’s also taught me so much about video, audio and streaming technology. It led me to getting my streaming studio to a place that’s really cool with all the cameras and all the audio equipment. I look back at the last eight months and I’m stunned with how much has happened. It’s amazing to think about.

What’s your home studio setup like?

Streaming-wise I started with my iPhone, I would just put it on the side of my piano use the built-in mic. It was fine, but I wanted to get more serious. That led me to talking to the guys at Zoom about their cameras. I got two Q2n cameras and I learned to do some basic streaming. Then I decided I wanted more cameras to have a variety of angles. Some of my streams are Steinway grand piano, and other streams are with my synthesizers. It’s a pain to have to reconfigure everything. I wanted to have cameras that are ready to go. So now I have five Zoom cameras around the room so I’m ready to start streaming at a moment’s notice. I’ve got one Q2n that faces down at my keyboard, one wide shot of the whole Steinway, a few cameras dedicated to my synthesizers. It’s a whole thing now.

How has it evolved over your career?

I realized I needed to have direct audio, where I can go from one setup to another and have it be really quick and easy, and make the whole thing seamless. I asked my engineer what he thought and he recommended the LiveTrak L-20 mixer. It’s been an incredible addition to my studio. If I want to do a piano and vocal stream, or if I want to do a synth stream, I just have to recall the scene I want and It mutes/unmutes the channels it needs to, adds the effects I want, and it’s all ready to go. It’s so seamless. I absolutely love it—it’s made my life so much better.

I loved it so much, I bought a second L-20 for my recording room. I have a separate room where I record my albums. I like to be able to play live with all my keyboards, but also work at my computer and know that I have everything routed in the right direction. With the L-20, I can go into my studio, decide what work I want to do, I hit one button and I’m there. This is a great thing when technology can function for you and work well. Life is awesome.

A lot of my work these days is done with a computer and software, but that said, I still use and enjoy all the different keyboards. I can’t deny it; I like being surrounded by keyboards. I wake up every morning and I say “Wow I get to play around with my synthesizers again today, what a great day!”

Would you like to share anything about any recent or upcoming projects you’re excited about?

On April 16, we have a very fun and highly anticipated Liquid Tension Experiment album coming out. It’s probably the most anticipated album I’ve ever done because we literally haven’t put out an album in 22 years.

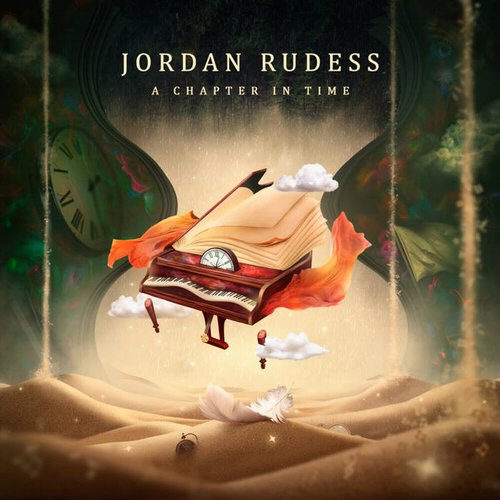

In other news, during this period of quarantine I finished an album of reflective piano music that I’ll be putting out on digital platforms very soon. It’s all finished musically—I’m just waiting for some graphics to come in. That album is going to be called A Chapter In Time. The music reflects on this period of time, so it’s gentle and thoughtful piano-based music.

At this very moment we’re recording a new Dream Theater album and it’s going really well. We’re having a lot of fun. That’s not coming out until next fall, so there’s some time to wait for that, but we’re really excited about the music we’re making.

What kind of advice or inspiration would you give to someone who wants to pursue a career in music?

Music is something that is so beautiful and nobody should be denied the right to make as much music as they want to make. It’s really important to set up your life so you can make music. Everyone has to make a living. Young musicians need to understand that making a living with music is one of the hardest things that anyone can take on. It’s fairly unlikely for most people, so understanding that going into it is a good thing. You want to set yourself up so you can make music happily. It doesn’t necessarily mean you have to do that for a living. Think about how you can set up your life so you can get the money you need and also have time to make the music. It is important to follow your heart. I’ve always done that.

Something else I recommend to people is how important it is to capture good video and audio. If you’re a band and you want to show someone your music, do it right. Get a Zoom camera or recorder—they allow you to capture your performances and rehearsals with a really great sound like nothing else. You don’t necessarily need to record direct with a mixer. Just put a Zoom camera in your studio and you’ll get great video and audio quality, and you’re good to go.